An interesting perspective on the B-29 by Tom Demerly, a journalist from TheAviationist, after his familiarization flight experience with the Commemorative Air Force’s B-29 Superfortress “Fifi”: https://theaviationist.com/2022/08/19/flying-on-fifi/

Dinah Might but Couldn’t Quite…

Sometimes a scale model kit comes along which fits into the scope of this web log. Such is the case with the recent (2022) Hasegawa release of a 1/72 scale model airplane kit, the late-war air defense fighter version of the Mitsubishi Ki-46-III Type 100 reconnaissance aircraft (Allied code name DINAH). This modified Dinah was a “stopgap” design to hold the line while Japan worked on specialized aircraft to deal with the USAAF B-29 Superfortress threat.

Although not a new kit, a re-release actually with origins going back to 2000 for the aircraft itself and the interceptor version, it does feature new decals and new box art featuring an aircraft of the “16th Company Independence Flight,” a unit assigned to Taisho Airfield near Osaka, now known as Yao Airport. (Note: “Independence” is probably better translated as “Independent.”)

The Ki-46 was well-known as a high-flying and fast reconnaissance aircraft. It seemed to offer some promise as a high-altitude interceptor. The Imperial Japanese Army’s Aerotechnical Research Institute (Rikugun Kokujigutsu Kenkyujo) developed a version of the Ki-46 as a high-altitude interceptor, with design studies that began in June, 1943 and active development from June, 1944.

The First Army Air Arsenal at Tachikawa (Tachikawa Dai-Ichi Rikugun Kokusho) accomplished the modifications for the aircraft which included creating space for two 20mm Ho-5 cannon and replacement of the top center fuselage fuel tank with a 37mm Ho-203 cannon angled to fire obliquely upward. This was a similar concept to some German Luftwaffe night fighters with their “Schrage music” upward-firing armament. It’s not clear how many Ki-46-III were converted to interceptor fighters at Tachikawa from the 609 Ki-46-III produced by Mitsubishi in their Nagoya and Toyama factories.

The first Type 100 air defense fighter (Ki-46-III KAI) was produced in October, 1944 and a month later the type began entry into operational service with several units. One of these was the 16th Independent Air Unit Squadron (in Japanese Dokuritsu Hikotai 16 Chutai – 独立飛行第16中隊 – literally Independent Air Unit Number 16 Squadron).

The chrysanthemum insignia on the tail indicates the 16th received a citation from the Emperor of Imperial Japan. IJAAF units known to display a chrysanthemum insignia include the 16th Dokuritsu Hikotai and 18th Hikodan Shireibu Teisatsu Chutai (18th Direct Command Reconnaissance Company).

Unfortunately for the Imperial Japanese Army, the Ki-46-III KAI didn’t have the climbing speeds needed to effectively intercept B-29 very heavy bombers, taking 19 minutes to climb up to 26,000 feet. Another criticism was that it “lacked stability for sustained shooting of the 37mm weapon.” Other critiques cite common design philosophy issues which favored long range and maneuverability over protection, e.g. thin armor plate, lack of self-sealing fuel tanks, which were fairly common features amongst Japanese aircraft then.

So, this new release by Hasegawa helps document the Japanese order of battle involved in the defense of Osaka, a welcome bit of detail, even if succinct.

References

“Belligerent Dinah” post at: http://www.aviationofjapan.com/2014/11/belligerent-dinah-17th-dokuritsu-hiko.html

Foro La Segunda Guerra, “Perfiles de Aviones de las Unidades Antibombardero Japonesas,” from lasegundaguerra.com website, posted on Pinterest, which indicated the 16th was at Taisho Airfield in December,, 1944, at:

Francillon, Rene J., Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War, Naval Institute Press, 1987, pp. 168-177

Hasegawa website page for this kit: http://www.hasegawa-model.co.jp/product/02401/

Ki-46 general information: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitsubishi_Ki-46

Livewarthunder.com shows an image and a nice color profile of this aircraft with following caption: “Mitsubishi Ki-46-III codename “Dinah” of the 16th Dokuritsu Chutai (later renamed 16th Dokuritsu Hikotai), Serial Number 24, based at Kiyosu Airfield at the beginning of summer in 1945.” At: https://live.warthunder.com/post/764565/en/

Pacific Wrecks Ki-46 entry: https://pacificwrecks.com/aircraft/ki-46/2783.html

Scalemates entry for this Hasegawa kit: https://www.scalemates.com/kits/hasegawa-02401-mitsubishi-ki46-iii-type-100-commandant-reconnaissance-plane-dinah-interceptor–1253046

Taisho Airfield: http://www.aviationofjapan.com/2012/07/taisho-airfield-101st-sentai-and-air.html

‘

The Osaka Source of “100 Atom Bombs”

This story and picture was posted in Instagram by combatpix on August 11, 2023 about Lt. Marcus E. McDilda, a P-51 Mustang fighter pilot assigned to the 46th Fighter Squadron of the 21st Fighter Group:

“On August 8, 1945, just two days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Lieutenant Marcus McDilda, an American P-51 fighter pilot, was shot down over Osaka and subsequently captured by the Japanese. Following his capture, McDilda endured mistreatment, including being blindfolded and beaten by civilians in Osaka.

He was then handed over to the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, who subjected him to interrogation and torture. The captors sought information about the atomic bombs, wanting to ascertain the number of bombs in possession of the Allies and their intended targets. Initially, McDilda maintained that he had no knowledge of the atomic bombs or the Manhattan Project.

However, faced with the threat of death, he eventually provided a false confession, claiming that the United States possessed 100 atomic bombs that would be deployed on Tokyo and Kyoto, the only Japanese cities he knew the names of, within a matter of days. McDilda’s confession contained a fictitious description of the science behind the atomic bomb.

In reality, the United States would not have had a third bomb ready for use until around 19 August and a fourth in September. McDilda’s false confession may have contributed to Japan deciding to surrender rather than prolonging the war. A few hours after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, the full Japanese cabinet met and debated surrender.

War Minister General Korechika Anami told cabinet that a captured U.S. pilot has “admitted”, under torture, that the U.S. possesses a stockpile of 100 atom bombs and that Tokyo and Kyoto would be destroyed “in the next few days”. As a result of his false confession, McDilda was considered a VIP person by the Japanese authorities and transported to Tokyo for further questioning.

There, a civilian scientist quickly realized that McDilda had no understanding of nuclear fission or the Manhattan Project. McDilda was eventually taken to a prison cell. Fortunately, he was rescued from the Ōmori POW camp 19 days later by the 4th Marine Regiment. The decision to move McDilda to Tokyo likely saved him from the fate suffered by 50 U.S. soldiers imprisoned in Osaka, who were executed by the Japanese.”

Lt. McDilda’s impromptu actions saved his life, and likely influenced senior leader decisions that ultimately saved the lives of many more, in Osaka, Japan, the United States and across Asia. He passed away in August 16, 1998 at the age of 76.

Additional Sources:

Fictitious description of atomic bomb, at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/85225209/marcus-elmo-mcdilda

“Oh! THAT atomic Bomb!” at: https://ww2aircraft.net/forum/threads/lieutenant-marcus-mcdilda-unsung-hero-of-world-war-ii.36172/

“…without warning of any kind, all hell broke loose” – the frontal penetration experience of Lt. Paul P. Schifferli, 5 May 1945

Sometimes the historical description of an event can be similar to that experienced by others in a similar time and place. Such is the case with a Facebook post in the “Fans of the B-29 Superfortress” group by Mr. Keith Schifferli, in honor of his grandfather, a B-29 pilot in World War II.

On December 10, 2021, Keith shared about his grandfather’s terrifying experience in a fierce weather front on the way to the Empire, during the daylight mission of May 5, 1945 against Kure and the Hiro Naval Aircraft Factory.

The description of Lt. Schifferli’s experience reminded this web log writer of the Osaka daylight mission of June 1, 1945, described in “The Osaka Mustang Massacre” post at: https://osakakushu.wordpress.com/2020/06/01/the-osaka-mustang-massacre/

In that Osaka mission several B-29s were lost in what may have been due to weather-related conditions. Lt. Schifferli’s survivor description vividly conveys the dangers of a frontal penetration, a situation in which these Osaka mission B-29s didn’t survive.

The urgency of the B-29 air campaign against the Empire was such that planes and crews were pushed to their limits in order to bomb the Empire into submission and avoid the need for a costly amphibious invasion of the Home Islands. Lt. Schifferli’s account is well-worth a read and a reflection on the pressures and costs of war.

“My grandfather, Paul Schifferli, was a B-29 pilot with the 20th Air Force, 73rd Wing, 498th Bomb Group, 873rd Squadron. In his memoires, he mentions the name of his planes were Mighty Fine and Mighty Fine II.

Here’s an excerpt from his memoires on the incident – “I had just completed tightening the final strap when without warning of any kind, all hell broke loose.

The plane had run into the violence of a huge thunderhead that first drove it downward, then lifted it with unparalleled force, flipping the seventy ton craft over on its back and into a loop that started us down toward certain destruction into the sea. At first the airspeed dropped to 70 mph, then it wound up to 400 mph as we headed down out of control. The initial thrust of the g-forces seemed to all but crash me against the ceiling, then as we flipped up and over I was pinned to the floor. My first reaction was disbelief, for I could not even move my hands, which seemed fastened to the ceiling, and then I realized we were in deep trouble. Up in the cockpit Lt. Tunnel also was fighting for his and our lives. As he started for the ceiling during the initial downdraft, he managed to lock his legs around the wheel and then as the ship looped and started down he and the co-pilot found, the strength needed to pull us out to level flight. But it was a very near thing.

Among the maneuvers prohibited in a B-29 were the following: a loop, spin, inverted flight, roll, vertical bank, and a dive in excess of the redlined 300 mph indicated. These restrictions were dictated by the strength limitations and control characteristics of the aircraft, for as the speed increased the loads carried by every part of the airframe and wings mounted rapidly, especially on the horizontal tail surfaces. In this dive we went through at least four of these movements, and it therefore was a wonder that the plane was not literally torn apart by the stresses put upon it. The fact that it did not disintegrate and crash illustrates to my mind that model of counseling attributed to St. Ignatius of Loyola; act as if everything depended on yourself, pray as if everything depended on God. The skill of the airframe designers and the determination of Lt. Tunnel and his copilot illustrated the first part of the doctrine, while the other nine crewmen no doubt were busy sending signals to the Deity in the clear.

We had fallen from 18,000 to 2,000 feet in well under a minute, the plane was a shambles, and eleven badly shaken men tried to decide what to do next. It was determined to head for Iwo Jima as quickly as possible, because there was no way to assess structural or mechanical damage to the plane. But there was much immediate evidence of the stresses the aircraft had endured. For example, when the plane first went downwards, the bomb load of seven 2,000 pounders sheared off their racks and partially crushed the communications tunnel between the flight deck and the central gunner’s stations. Then as the plane was thrust upwards, the bombs fell free, taking the bomb-bay doors with them. These same forces rendered every gun aboard useless, because the linkages simply burst out of their canisters, and 9,000 rounds of ammunition flew all about. The best example of the forces endured relates to the radio operator’s equipment. The radio sets literally broke their bolts and rammed through the top of the plane, where they remained to the wonderment of all as we inspected the damage.

The most grotesque wreckage, however, was found in the rear just outside my compartment door. There the signaling shells broke out of their canister, fragmented but did not explode, and spread their golden powder over the entire rear section of the plane. When I came forward from my station about an hour later, I thought that this might be a gilded movie set, and that the chorus girls in some dance sequence of a Busby Berkeley musical would soon appear. This fantasy quickly faded when I entered the radar operator’s section, for the latrine had emptied its contents all over this area.

Moving quickly into the central gunner’s section I saw more evidence of near disaster with equipment scattered everywhere. Since the gunners there were in no mood for talking, I simply continued forward through the crumpled communications tube. Had anyone been in it at the moment of the accident, he would have been seriously hurt or killed. I then reported to Lt. Tunnel that so far as I could tell, the rear of the plane was still airworthy, but was an incredible mess and utterly defenseless.

The navigator got us back to Iwo by means of a sextant and dead reckoning, and we landed without incident. We then became the center of attention from ground personnel and Marines as they marveled at the damage. The craft literally had a slightly bent fuselage in the manner of a broken back, and it looked as if it would never fly again. In fact, it never flew another mission, for it was ferried back to the Guam Air Depot, surveyed and returned to the United States as irreparable.”

Thanks to Mr. Keith Schifferli for permission to share his grandfather’s riveting account!

To the End(s) of the Empire – B-29 Aircraft Commander Edward Vincent of the 6th Bomb Group

As Imperial Japan surrendered on this day 75 years ago, 15 August 1945, Lt. Edward Vincent of the 6th Bombardment Group (Very Heavy) was the youngest B-29 aircraft commander of World War II at the age of 21. He flew a total of 32 combat missions over the Empire by the time the war ended including the longest one of the war from the Marianas to the northeast coast of Japanese-occupied Korea, some 19 hours and 40 minutes in the air!

In this video heavily illustrated with period photos, Edward Vincent provides an insightful overview of his experience which ultimately helped bring an end to the Second World War. You will note the well-known photo of the B-29 over Osaka Castle at the 14 minute mark.

In 2015, the writer of this web log was fortunate to join a 6th Bomb Group reunion held in Portland, Oregon. Some highlights from the reunion, including some more information about Edward Vincent, are in the article posted on the 142d Wing website at:

The Dangers of Airfielding Around Osaka

The pressure on Imperial Japan was ever increasing in the summer of 1945, as Allied forces closed in on the Home Islands. Osaka experienced a number of air attacks in addition to the B-29 missions flown against the city. Seventy-five years ago, on 30 July 1945, three USAAF very long range (VLR) fighter groups based at Iwo Jima, the 15th, 21st and 506th, carried out a sweep of the skies around Osaka and nearby Kobe, looking for any aerial opposition.

Despite the approximately one hour of time each group spent over Japan, there was little to show for it. Seven Japanese aircraft were sighted, all too far away to engage in combat. But the fighters also looked for targets on the ground and conducted rocket attacks against Hanshin Airfield and strafed airfields at Itami, Sano and Kakogawa. In addition, they made observation of activity at Osaka East, Minato, Tambaichi and Nishinomiya airfields while at low level. The P-51 pilots only sighted five operational aircraft on all these airfields.

By this time in the war following the Battle for Okinawa, indeed, for much of July 1945, the Japanese deliberately avoided air combat in an effort to save aircraft for the anticipated Allied invasion of the Home Islands. Enemy airfields were either empty, or dummy and/or non-operational aircraft were spotted around as decoys, while the Japanese made great effort to disperse and camouflage operational aircraft. The military clique fully intended to fight to the bitter end. So for the VLR fighter pilots July proved to be a frustrating month for engaging their counterparts. attacks against various airfields in the area, including Hanshin.

Despite the lack of aerial opposition, it was still costly to go “airfielding” around Osaka. On this mission two P-51s were shot down and the pilots missing. Another brought down by enemy guns but the pilot was rescued from the sea. Two more were lost to operational conditions but both pilots were rescued. In addition to the five losses, seven other Mustangs were damaged.

One of the pilots lost on this mission was 23-year old 1st Lt. Harry W. Norton, Jr. of the 21st Fighter Group, 72nd Fighter Squadron. He was last seen at low altitude over Osaka in an aircraft damaged from ground fire. One source (Find-a-Grave entry) indicates he survived, was captured and later executed by the Japanese military. For other information about his loss see an earlier post at: https://osakakushu.wordpress.com/2015/05/24/memorial-day-2015-remembering-the-last-flight-of-harry-w-norton-jr/

The other Mustang pilot lost that day was Captain Walter H. “Sammy” Powell, (acting) commander of the 47th Fighter Squadron. Well-regarded by the members of the “Dogpatch Squadron,” named after the fictional setting of cartoonist Al Capp’s famous comic strip “Li’l Abner; he led the 16 aircraft of his squadron on this mission.

Capt Powell enlisted in the Air Corps in May, 1942, and then trained to be a pilot. He received his pilot’s wings and commission as a second lieutenant on Feb. 16, 1943, at Spence Field, Moultrie, Georgia. The next month he was assigned to 7th Air Force in Hawaii. In April, 1943 he joined the 15th Fighter Group so was well-experienced in the unit. He was promoted to first lieutenant on Nov. 2, 1942, and to captain in January, 1945.

Captain Powell was in the first fighter squadron of P-51 Mustangs to land on Iwo Jima in early March, 1945. His squadron made continuous raids over the Japanese homeland. Powell served as the 47th FS Operations Officer and was credited with a single aerial victory, perhaps against a ZEKE on 10 June 1945 during an escort mission to Tokyo. He became acting commander on 11 June 1945 when the 47th FS commander Maj Theon E. Markham was granted a 30-day leave in the States, and then was shot down and rescued by a US Navy submarine. Since the submarine was scheduled on station for a while, the commander was stuck for a while (Maj Markham resumed command on 5 August), so Powell’s acting commander role lasted for a while before his fateful mission. He had celebrated his 27th birthday only days before, on July 24.

Interestingly, a scale model decal sheet by AeroMaster, Pacific P-51D/K Mustangs, carries markings for a P-51D-20NA, serial number 44-63822, that Capt Powell flew earlier in 1945, named “Lil Butch.”

On the Sano mission however, he reportedly flew number 188, named “Adam Lazonga.” The decal sheet shows the colorful blue stripe outlined in yellow markings “Lil Butch” and the 47th Fighter Squadron used (Note, several other modeling reference indicates “Lil Butch” markings were black with yellow outlines):

On 30 July 1945 it was Fighter Strike Sano A/F, tasked in Field Order No. 154, 15th Fighter Group Mission # 7-, 47th Fighter Squadron Mission # 7-21. Captain Powell led the other 15 pilots of the squadron, all lieutenants. Red, Yellow and Blue flights had four P-51’s each, with a two-ship reserve for Red Flight, and two more Mustangs in a Pearl Flight that flew with the 45th Fighter Squadron.

Sano Airfield was located along the coast south of Osaka nearly opposite of the Kansai International Airport island built in Osaka Bay. The site of the former airfield is near the Nankai Railway’s Izumisano Station, right before the tracks steer to the right and head into Rinku Town and then across the bridge to Kansai International Airport. It was reportedly constructed in 1945 by local elementary and junior high school students. One source indicates Sano served as a training field for kamikaze pilots, who then shipped out to other bases for their final missions.

Another source, scale modelling and a decal vendor Rising Eagles from the Czech Republic, Sheet Emperor’s Eagles Part IV., indicates that in this timeframe there was an IJAAF fighter unit based at Sano, the 55th Sentai equipped with Kawasaki Ki-61 TONY fighters, as indicated in three specific aircraft examples:

3) Ki-61-I Tei, 55th Sentai, Sano Airfield, Osaka Prefecture, Honshu, August 1945

4) Ki-61-I Hei “06”, 55th Sentai, Sano Airfield, Osaka Prefecture, Honshu, August 1945

5) Ki-61-I Hei “03”, 55th Sentai, Sano Airfield, Osaka Prefecture, Honshu, August 1945

Instructions for the decals show KI-61 aircraft in camouflage (acft 3) and natural metal finishes (acft 5 & 6)

A 1/48-scale model of a Ki-61 Hien/TONY shows the natural metal finish version at Sano nicely:

The 15th Fighter Group arrived over Honshu at 13,000 feet and began its work. First the 78th Fighter Squadron attacked Hanshin Airfield as the 47th and the 45th Fighter Squadrons flew top cover. The squadron then flew towards Kyoto looking for enemy aircraft and after sighting none, turned west and arrived east of Osaka, then southwest to Sano Airfield. There both the 47th and 45th strafed the field while two flights of the 47th strafed a factory west of the field, encountering light machine gun fire. The 47th’s Red and Yellow Flights flew down the coast while Blue Flight remained at Sano for top cover as the 45th FS attacked the field. While looking for targets on the coast, Yellow Flight attacked two more factories and a powerhouse while Red Flight attacked a small vessel, a “Sugar Dog” and received heavy machine gun fire in return. Altogether the squadron expended 15,700 rounds of .50-caliber ammo on the mission.

After flying about 25 miles down the coastline Capt Powell’s P-51 exploded, with a 2 x 4 feet of fuselage skin blasting off between the tail and the wing. In the P-51, oxygen cylinders are abaft the cockpit and could possibly cause such an explosion inside the aircraft. Flight members saw the event but did not observe any flak in the area when it happened. At the time the flight was at 2,200 altitude and with a stricken aircraft Capt Powell turned over his flight to his element leader to lead them to a designated rendezvous point with the rest of the squadron and called for help from Airdale 722 as Powell focused on his wounded bird. Coolant was leaking and Powell couldn’t keep up with the squadron as his engine began overheating as Lt. Barlow (Red 4) remained with him and they headed out to sea to avoid capture by the Japanese.

Powell’s Mustang consumed itself as it steadily lost altitude; the coolant door blew off and flames started coming from his engine exhaust stacks. The canopy frosted over from the fire and smoke and Powell jettisoned it. At 800 feet he rolled it over on its back and then Split S. At this point it seems he attempted to get out butt the aircraft went out of control as it snap rolled, half rolled and went straight into the sea and sank immediately.

Yellow 2, Lt. Sparks recalled in 1995 that he came back down through a layer of clouds to check on the situation that he saw Powell try to bail out at around 500 feet.

“He couldn’t away from the airplane,” Sparks said. “It was in sort of a flat spin. He got out of the cockpit but didn’t get away from the plane. I kept screaming at him to jump, but of course he couldn’t hear me. I think he went in, still on the wing of his airplane.”

Powell was not seen to bail out though his life raft, seat cushion and parachute were observed just under the water as Red flight circled the crash site. Red Flight orbited the site for 30 minutes and had to leave for Iwo Jima leaving a Super Dumbo B-29 to search for Powell. With a rescue submarine on the way. Red Flight arrived at the RP late and missed a navigating B-29 steering the squadron on the long three-and-a-half hour flight home, and Red 3 and 2 flew back to Iwo together. Lt Barlow lingered longer over the crash site and returned to Iwo alone.

Powell was never found and is carried as MIA to this day. Fifty years after his loss, squadron members still recalled it with sorrow, and also some difference of opinion as to what happened. One pilot thought friendly fire struck his aircraft while strafing, being hit by .50-caliber bullets that ricocheted off the ground as the Mustangs strafed.

Video (35 seconds long) of P-51 Mustangs strafing airfields in Japan, at:

Another pilot recalls they strafed a ship in a harbor and guns from the ship and shore hit the aircraft. Either way, the damaged aircraft only went so far before falling into the sea about 15 miles off shore in the Kii-Suido Strait on the south side of Osaka Bay.

Sadly, his wife Susi learned of his fate while expecting birth to their child. A letter from the squadron arrived at the Powell home on August 12, 1945 carrying the awful news. The shock hit Susi Powell hard, and she didn’t give birth for another week, to a baby girl she named after her late husband and a family member, Henry Verleene Powell. Even though she remarried after the war, Susi never forgot her pilot husband. Fifty years didn’t erase her sense of loss at losing him as she recalled in a 1995 interview with the Daily Press: “You just cannot imagine what I go through every time I see an airplane, or think of all the fun we used to have riding motorcycles,” she said. “We built the first dirt track in Hampton. We used to have a good time.”

Capt Powell is remembered in the Courts of the Missing, Court 7 at the Honolulu Memorial; He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with 2 Bronze Service Stars and World War II Victory Medal.

So although there was no aerial opposition to speak of, this mission to the Empire was still costly for aircraft operating over the Osaka region. How much more effort would be required to subdue a stubborn Imperial Japan? No one knew at the time, but the pressure was building as more and more units on air land and sea arrived in the Pacific to do just that. And Osaka would be pressured again and again from the air in the near future.

References

7th Fighter Command Association webpage at: https://www.7thfighter.com/

47th Fighter Squadron history, at: https://www.afhra.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/434059/47-fighter-squadron-afrc/

“Lil Butch” decal information, at: https://iwojimamodels.com/2020/01/29/decal-review-aeromaster-pacific-p-51d-k-mustangs-48-012/

1/144 P-51 D image, at: https://kenny22.com/p51d-144/

1Lt Harry W. Norton Jr., “Find-a-Grave” tribute page at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/68451951/harry-walter-norton

Capt Walter H. Powell, “Find-a-grave” tribute page at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56119535/walter-h-powell

Newspaper account of Powell’s loss, at: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/35805321/daily-press/

Official History of the 47th Fighter Squadron, June and July 1945, at: https://www.7thfighter.com/

McMichael, William H., “Final Flight,” Daily Press, 30 July 1995, four page story with more personal recollections and Capt Powell background at: https://www.dailypress.com/news/dp-xpm-19950730-1995-07-30-9507300108-story.html

Info on Sano Airfield near Osaka, at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2005/08/11/national/memories-of-war-alive-at-old-military-sites/

Info on aircraft at Sano Airfield, at: http://www.rising.risingdecals.com/index.php/1-72-decal-sheets

1/48 Scale Model of 55th Sentai Ki-61 in NMF, at: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/hyperscale/kawasaki-ki-61-i-tei-hien-hasegawa-1-48-t52251.html

The Day a Pumpkin Dropped on Osaka

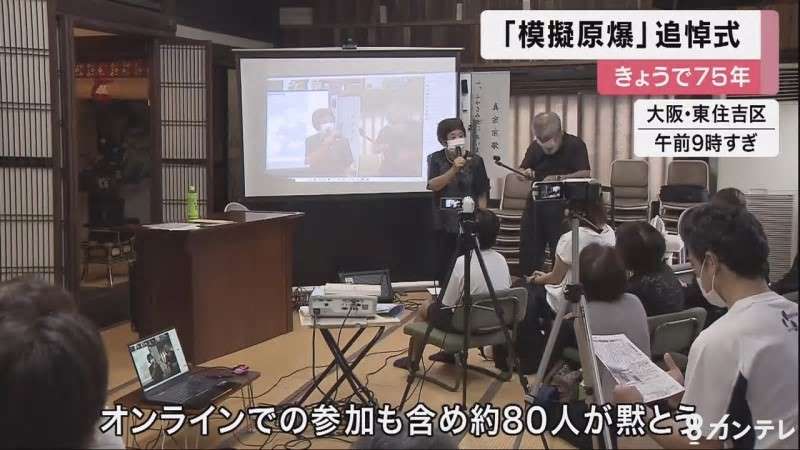

It was a Thursday morning, July 26, 1945, and the day the Potsdam Declaration would be issued. But in the skies over Osaka, a single “Pumpkin” was released at 0946 local time from a 509th Composite Group B-29 flying at 30,000 feet over the city of Osaka. The aircraft then executed a sharp turn to the right 150 degrees away from the original flight path as required for aircraft survival in delivery of an actual atomic weapon. The non-atomic “Pumpkin” bomb fell to earth and exploded 50 seconds later in the Tanabe part of Higashi-Sumiyoshi Ward of Osaka City.

In the weeks preceding the atomic bombings of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9), the 509th Group B-29s flew 50 sorties carrying “Pumpkin” bombs, a sort of pumpkin-shaped conventional version of the “Fat Man” type of atomic weapon dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945 (Hat tip to Mr. Jeffrey Smith for correction, Hiroshima device of 6 August was “Little Boy”). Of these, 49 bombs were dropped on targets in Japan in what were considered training missions (one aircraft experienced an engine problem and jettisoned the weapon into the ocean). Both visual and radar weapons deliveries were conducted, as can be seen in this 509th mission list from a Japanese website:

Source: https://www.onrakuji.com/%E6%A8%A1%E6%93%AC%E5%8E%9F%E7%88%86%E8%B3%87%E6%96%99%E9%A4%A8/

You will note on the mission list above that Osaka Prefecture appears twice, once on 24 July (Sortie 19, Visual, of Mission 7, looks like maybe Sakai City, a large suburb on the south side of Osaka City) and again on 26 July (Sortie 29, Visual, of Mission 9, Osaka City proper).

These Pumpkins were real bombs, with the same ballistic and handling characteristics of the “Fat Man” atomic bomb, but used for testing and training purposes; 486 were produced in inert (non-explosive) and explosive versions costing between $1,000 and $2,000 each. The Pumpkin was 10 feet and 8 inches long, up to 60 inches wide. It weighed weighing some 11,700-pounds (5.89 short tons) which contained 6,300-pounds of Composition B explosive filler (another source indicates 5,500 pounds of black powder or Torpex). The weapon was carried in the forward bomb bay of a Silverplate-modified B-29. It had three fuses on the nose which could detonate the bomb above the ground to maximize the blast against the surface.

More than just training aircrews in atomic weapons delivery, the Pumpkin missions were also intended to desensitize Japanese air defenses to single or small formations of three B-29’s from which only one dropped a weapon. This too was in the template for the intended atomic bomb strikes, with one plane carrying the weapon, another an instrument ship to record the bomb’s detonation and another aircraft as a photo ship to visually document the event. By this point in the war the Japanese were carefully conserving their aircraft, and though some fighters were sighted during Pumpkin missions there is no reported interception by any of them. Flying at 30,000 feet also limited the effectiveness of anti-aircraft guns, which appear to have conserved ammunition and posed no serious threat to the Pumpkin missions; only one B-29 received minor damage from AA guns.

A total of 49 Pumpkins were dropped over Japan on four mission days in July, 1945 and two more mission days in August on numerous different areas/locations, as can be seen in this graphic from a Japanese website:

Source: https://www.onrakuji.com/%E6%A8%A1%E6%93%AC%E5%8E%9F%E7%88%86%E8%B3%87%E6%96%99%E9%A4%A8/

After the first Pumpkin missions were flown on 20 July, Radio Tokyo commented on a Pumpkin dropped on the capital: “The tactics of the raiding enemy planes have become so complicated that they cannot be anticipated from experience or the common sense gained so far. The single B-29 which passed over the capital this morning dropping bombs (sic) on one section of the Tokyo Metropolis, taking unawares slightly the people of the city, and these are certainly so-called sneak tactics aimed at confusing the minds of the people.”

Sifting through various websites and information, it appears that on 26 July it was 1st Lt. Ralph Devore and crew A-3 which flew the Pumpkin bomb mission to Osaka with “Jabit III,” a name later given to B-29-36-MO 44-27303 (see Jabit III Wikipedia link below). But another source, the Operations order for 26 July indicates that Devore flew B-29 with the tail number 299 and Victor 6 code that day, and that B-29 44-27303 wasn’t on the schedule that day. (Hat tip to Mr. Mike Mack) Was there a schedule change?

At the time in late July 1945, 509th aircraft all had the original group insignia of an arrow in a circle tail marking. The circle was a common 313th Bombardment Wing tail marking there on Tinian where the 509th was assigned. In early August, just before the Hiroshima mission, it was decided to adopt the tail markings of other groups on Tinian, and different (higher) Victor numbers marking to try and blend in with the other groups and not stand out so much. (Hat tip to Mr. Mike Mack) After that change, B-29 44-27303 then wore the large letter “A” tail marking of the 497th BG as a security measure against 509th identification.

The B-29’s approach was made over Shikoku, then eastward to the Nara area. The original intended target was the Nippon Soda Co., Ltd. (Chemicals: Nihonsoda) in Toyama on the Sea of Japan side of Honshu, but that didn’t work out for some reason so the aircraft turned for an alternate target with visual conditions which was Osaka. It may have triggered an air raid alarm but it wasn’t seen as a serious air raid and appears it was more or less shrugged off.

Another source indicates there was no air raid alarm in the local area where the bomb fell. A Mr. “O,” an elementary school student at the time, saw the B-29 appearing alone over Osaka: “The air raid warning didn’t go off, When I thought that the appearance was different for the air raid, it dropped something with a parachute and turned back immediately. Is it the sound of a parachute? I still hear the sound of a wind cut.”

But it was a raid and the object dropped was serious. The Pumpkin that fell on Tanabe may have been employed as an operational training device but it was still a deadly weapon for the people on the receiving end. When it exploded low over Osaka directly over the restaurant “Kongoso” the blast and concussion killed seven people and seriously injured another 73. It destroyed and/or damaged some 485 houses wounding/affecting 1645 other people. Onrakuji Temple, located about 200 meters from the hypocenter of Higashi-Sumiyoshi-ku, was slightly tilted by the blast from behind the main hall. It is still tilted as it was that day.

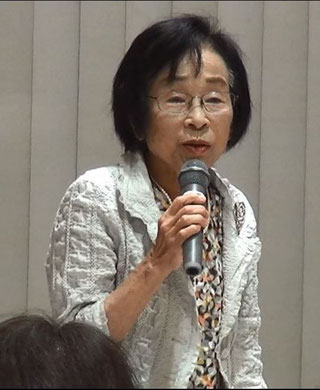

Ms. Shigeko Tatsuno survived the attack at a factory 150 meters to the west of the center of the impact and remembers what happened (apology for crude translation): “I was a junior high school teacher at the time, and led students in labor mobilization to navy button manufacturing factories around Tanabe. However, I couldn’t work due to lack of materials, so when I moved to another room and tried to teach, a big stone flew into the factory. If I hadn’t moved… A stone that I couldn’t lift with both of my hands broke through the roof in the place I was in before I moved. Later, it was discovered that the simulated atomic bomb dropped in front of the current Tanabe subway station caused the stones at the restaurant near the hypocenter to fly.

In addition, it seems that the bodies of the dead and injured were lined up in the auditorium of Tanabe Elementary School, and dust and blood clung to it. A story of people whose limbs were blown off by a blast, and the flesh of a human body hanging on an electric wire. An important friend (her sister’s best friend) who was blown 150 meters by the blast and died full of glass fragments all over her body. I removed the glass from my friend’s body with tweezers and chopsticks in a praying mood.

Tell the children about the foolishness of war, where a single bomb can kill lives in an instant. Every year, I hear my whole body listening to Ryuno-san’s war experience, and I feel hope from the bottom of my heart at the serious eyes of elementary school students who try to learn through repeated questions. And said to the students “During the pre-war, we were foolish enough to believe that Japan was right. You should grow up to be able to think and act on your own what is really right.””

At the time, it was rumored that a “one ton bomb fell” in the local area and caused the destruction. Only years later did awareness of the Pumpkin bomb operational missions and connection to the atomic bombings occur. Some 400 people on the ground were killed across Japan in the 49 Pumpkin attacks.

In Osaka a memorial stele and information display was erected in 2001 near the point of impact of the Osaka Pumpkin, initially placed near the present north side of Tanabe Elementary School near Tanabe Station on the Osaka Tanimachi Line.

The monument was apparently moved in 2019 to the Onrakuji Temple (at Tanabe 1-14-18) due to construction of an apartment building at the original site.

Memorial services for the victims of the 26 July Pumpkin drop are held annually by the “7/26 Tanabe Mock Atomic Bomb Memorial Committee” created by local citizens. These commemorations tell what happened that day, about the link the Pumpkin missions had with the atomic bombings along with calls for peace.

This year at the memorial service about 80 people participated including those who participated online due to the influence of the new Coronavirus. Ms. Tatsuno, now 95 years old, spoke to those attending. All offered a moment of silence at 9:26 a.m., the moment when the bomb was dropped, to the victims of the Pumpkin drop 75 years ago.

But in 1945, peace was yet to come in the Pacific. Another three weeks of war was still ahead, and Osaka would not be spared in these last days.

References

Pumpkin bomb, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pumpkin_bomb

Pumpkin bomb replica in color, at: http://www.asiapress.org/apn/2015/10/japan/301-02/

Polmar, Norman, The Enola Gay: The B-29 That Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima

B-29 44-27303 “Jabit III” at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jabit_III

More images and information, video, at: https://www.onrakuji.com/%E6%A8%A1%E6%93%AC%E5%8E%9F%E7%88%86%E8%B3%87%E6%96%99%E9%A4%A8/

Memorial and bomb damage recon photos: http://hiranogou.cocolog-nifty.com/blog/2011/08/post-775f.html

Memorial and 1948 aerial picture at: http://hiranogou.cocolog-nifty.com/blog/2011/08/post-775f.html

75th anniversary memorial service (including video) at: https://www.fnn.jp/articles/-/66764

Mr. O quote on the attack: https://www.daily.co.jp/society/life/2020/07/25/0013542676.shtml

Double Whammy and a Kick on Osaka, 24 July 1945

In this web log the number of major B-29 attacks against Osaka is counted as seven. This is based on the US Strategic Bombing Survey of the results of US aerial missions flown against targets in the city. There were four area and three precision attacks. Source: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/NHC/NewPDFs/USAAF/United%20States%20Strategic%20Bombing%20Survey/USSBS%20Effects%20of%20Air%20Attack%20on%20Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto.pdf

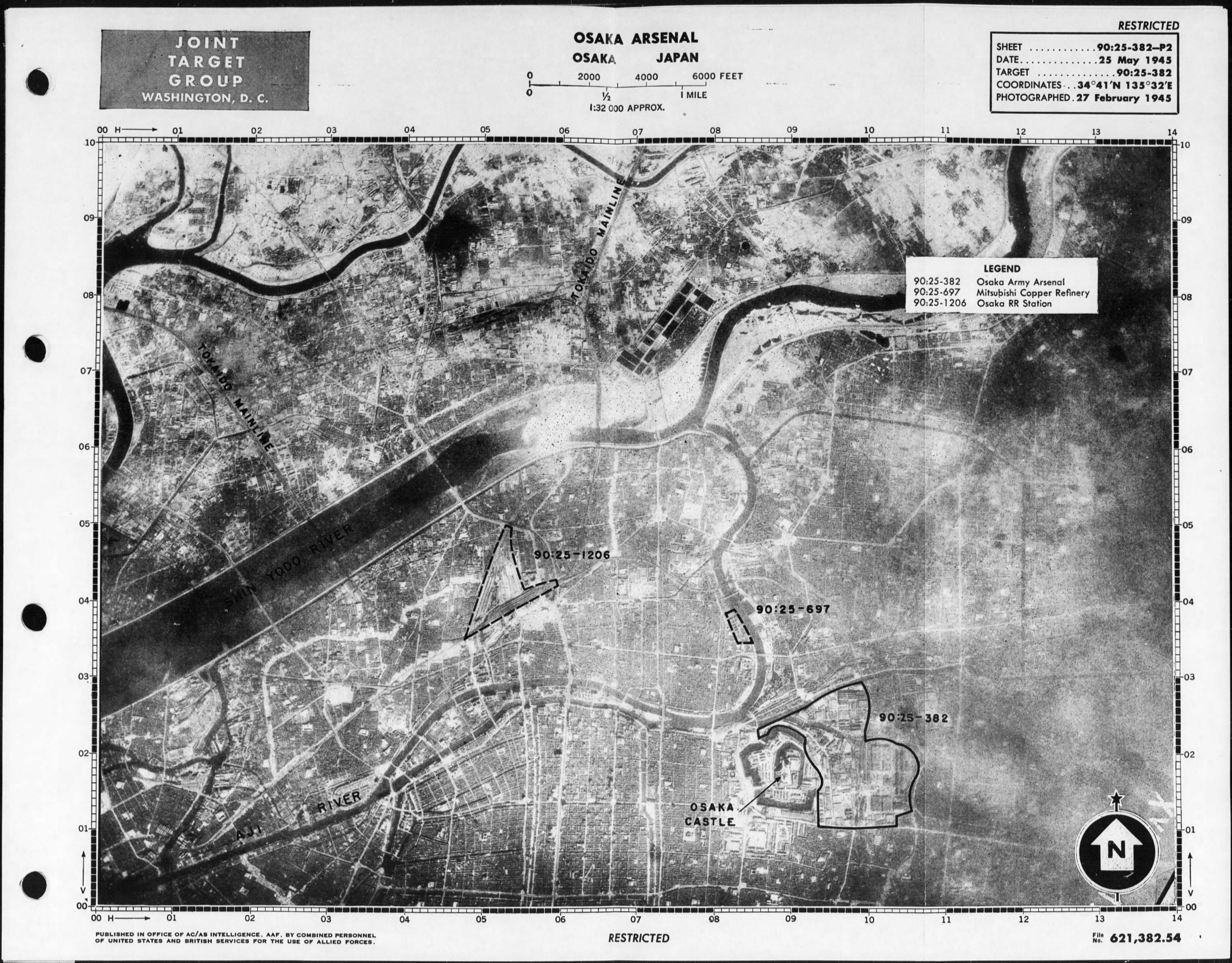

The USAAF mounted a B-29 air attack against two different targets in Osaka on July 24, 1945, 75 years ago today. Like the 26 June precision attack, both the Sumitomo Light Metals Company in the western section of the city and the Osaka Army Arsenal immediately to the east of Osaka Castle were the targets.

In XXI Bomber Command Mission 284, 82 B-29’s from the 58th Bomb Wing attacked the Sumitomo Light Metals Industries propeller factory at Osaka (Target 90.25 – 263A), near to Osaka Bay on the city’s northwest side. Most of the factory’s machine tools had been removed by this time in the war but the facility was severely damaged in this attack.

Weather impacted the mission only slightly with an undercast of up to 3/10. The aircraft dropped 488 tons of AN-M56, 4000-lb L.C. (Light Case) bombs with instantaneous nose and non-delay tail fuzes. The bombs were released from between 19,900 and 22,100 feet in altitude between 1251-1322K. That amounted to 244 big bombs, with 115 of them falling within 1,000 feet of the desired Main Point of Impact (MPI) damaging about 77% of the factory and raising the overall damage level from earlier attack to nearly 90%.

Of the aircraft attacking, heavy caliber anti-aircraft fire which carried between moderate and intense , and accurate, shot down one B-29 and damaged 50 others to various degrees. No enemy aircraft were seen.

The B-29 lost was from the 444th Bomb Group (Triangle N), 677th Bomb Squadron’s based at West Field on Tinian, serial number 44-70132 with the Seymoure Crew. MACR 14792. Flying at 19,450 feet, it was hit by flak one minute before bombs away and immediately broke into two pieces over Osaka Bay with both parts landing in the waters below. No crew from the front end of the ship were seen to exit, though three men were observed to clear the plane from the rear. One chute was seen opened and the man appeared to be ok. A second man had his parachute on, appeared to be completely relaxed but his chute was not seen to open, whilst a third man has his knees double up and arms thrust (outward) but his chute was not seen to open.

As things turned out, ten of the crew were killed and the one survivor, Co-pilot 2nd Lt. James R. Price was captured, moved to the Osaka Kempei Tai Headquarters and later poisoned there on/about July 31 (along with SSgt Russell W. Strong from another crew, possibly the radar operator of the Crowe crew of B-29 42-65348, A Square 16 of the 869th Bomb Squadron, 497th Bomb Group shot down on the 1 June 1945 Osaka mission) supposedly because of his fatal wounds.

A postwar legal document on the trial of accused war criminals described what happened from the testimony of one of the accused, that a second execution of POWs by poisoning took place on/about July 31, when two prisoners (Price and Strong) reportedly suffered from diarrhea. Lt Col Fujioka, Chief of the Police Affairs Section of the Central District (Osaka) Kempei Tai headquarters, ordered them to be poisoned. Their captors mixed poison into some stomach medicine – the men drank the laced medicine and died a few minutes later. Their bodies were then taken to Sandayama Army cemetery and buried, along with the bodies of two other fliers who had suffered a contagious disease and were also poisoned, Navy Ensign Norman B. Bitzegaio (Torpedo Squadron 6 (VT-6), USS Hancock, awarded the Navy Cross for actions 24 July 1945 against the Japanese Fleet in Kure, Japan) and an unidentified man, possibly a P-51 pilot.

Co-pilot Lt James Robert Price was buried in Danville National Cemetery, Danville, Boyle County, Kentucky, at Plot 11, 0, 376. Nine members of the crew were buried in a common grave at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in Missouri; Navigator 1st Lt Wendell D. Copeland was buried/remembered at Lynnhurst Cemetery, Knoxville, Tennessee, Pillar VII, Middle Panel.

In the second raid that day to hit Osaka proper, Mission 286, 153 73rd BW B-29’s hit the Osaka Arsenal (Target 90.25 – 382 as Primary Visual target) and Kuwana (near Nagoya, Primary Radar); solid undercast forcing most of the attackers to resort to radar bombing against Kuwana. A “Wind-Run” aircraft was also employed for the Primary Radar target (at Kuwana) ( a “wind run” B-29 could be sent in advance to the target a few minutes early and broadcast the drift encountered provided the following crews with preliminary values of drift angle and ground speed as they came up on the Initial Point. (Wind Run source: http://www.315bw.org/anthologies.html )

The 35 B-29s which dropped on Osaka Arsenal between 1144-1227K delivered 216 tons of AN-M66 2,000-lb General Purpose bombs with 1/40 second delay in nose and tail fuzes. Of the 216 bombs dropped from between 19,900 and 23,000 feet on the arsenal, 28 hit within 1,000 feet of the MPI. Strike photos showed several hits in the target area and immediately south and west of the target. Several bombs damaged Osaka Castle.

Post-attack recon showed over 8% of the target damaged in the raid which raised the cumulative total destroyed of the arsenal to 18%. No enemy aircraft were sighted. Over Osaka anti-aircraft fire was moderate, accurate and continuously pointed. A total of 46 B-29s from both Osaka Arsenal and Kuwana raiders were damaged.

Navigator Ray Brashear succinctly noted in his diary for his Mission number 34: “Osaka Arsenal Day demo(lition)… Flak —Mod , accurate. Fighters—nil. Lead a group of 47 planes after ass’y at Kita Iwo. 5/10 over target so only 3 Sq in wing bombed primary. This one made believers out of a few of the new boys.”

In addition to the above, another B-29 effort (Mission 285) was flown against the nearby Kawanishi Aircraft Plant at Takarazuka which produced component parts for various Kawanishi aircraft (e.g. George fighter, Emily flying boat). Takarazuka is just northwest of Osaka, about five miles west of Itami Airfield, known as Osaka International Airport in modern days (and the former USAF Itami Air Base). Eighty one 58th Bomb Wing B-29’s hit the plant destroying 77% of it.

Of note, Allied naval aircraft from Task Force 38 (US Third Fleet) and Task Force 37 (British Pacific Fleet) attacked targets around the Inland Sea. Though many of the 1,363 US sorties were flown against the major Japanese naval base at Kure, many other sorties were flown against airfields and shipping all around the Inland Sea. TF-37 flew 257 offensive sorties on the day as well, though details are lacking to the web log writer regarding Osaka area effects.

Lastly, though it seems hard to find information on, it appears that Osaka was also subjected to a “Pumpkin” attack on this date, by a B-29 of the 509th Composite Group, possibly “Jabit III,” serial number 44-27303 flown by the Devore crew (Crew A-3) a Project Silverplate B-29 nuclear bomber.

The “Pumpkin” was a pumpkin-colored and shaped conventional bomb of the size, shape and weight of the Fat Boy atomic bomb but which had a conventional high-explosive filler. Each loaded pumpkin bomb weighed about 10,000 pounds, including 6,300 pounds of explosives. These so-called “Pumpkin” missions were flown using the delivery profile of a B-29 atomic bomber, from about 29,000 feet and then a sharp break away after release to achieve safe separation from the weapons. Although details for this 24 July mission are lacking (hard to find), three 509th missions involving 10 aircraft on this day, they are available for a 26 July Pumpkin mission against Osaka to be covered in a future post.

With regard to damage on the ground, this raid on Osaka was the least destructive to residential units of the seven major B-29 attacks on the city, with “only” 654 residential units being destroyed or badly damaged. It was also the least costly in lives on the ground, with USSBS estimates of 201 dead, 193 missing and 466 injured. Contemporary Osaka figures show somewhat lower figures with 214 dead, 79 missing and 329 injured.

One more major air attack would be flown against Osaka during the war on 14 August 1945, which would be the Osaka Arsenal’s ultimate “Day of Wreckoning.”

References

XXI Bomber Command Mission Summary for 24 July 1945: https://user.xmission.com/~tmathews/b29/56years/missionsummary4507.html#24jul45

AN-M56 4,000-lb bomb info at: https://bulletpicker.com/bomb_-4000-lb-lc_-an-m56_-an-m.html

AN-M66 2,000-lb bomb info at: https://bulletpicker.com/bomb_-2000-lb-gp_-an-m66.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silverplate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pumpkin_bomb

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jabit_III

US Strategic Bombing Survey report for Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/NHC/NewPDFs/USAAF/United%20States%20Strategic%20Bombing%20Survey/USSBS%20Effects%20of%20Air%20Attack%20on%20Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto.pdf

US Strategic Bombing Survey report for Kawanishi Aircraft Company: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/NHC/NewPDFs/USAAF/United%20States%20Strategic%20Bombing%20Survey/USSBS%20Kawanishi%20Aircraft%20Co.%20Report%20No.%20III.pdf

Osaka bomb damage picture for damage to Morinomiya Station 24 July 1945: https://mainichi.jp/articles/20160804/ddl/k27/040/355000c

Herder, Brian Lane, The Naval Siege of Japan 1945 – War Plan Orange Triumphant, Osprey Publishing, Campaign 348, 2020

Lt Price memorial at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/1093438/james-robert-price

ENS Bitzegaio unit and award information at: https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/19784

Seymoure crew common grave at: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/42246876/philip-sagona

Lt Copeland memorial at: https://etvma.org/veterans/wendell-d-copeland-7707/

Trial Proceedings against accused war criminals for treatment of fliers in Osaka region: https://www.online.uni-marburg.de/icwc/yokohama/Yokohama%20No.%20T328.pdf

Tabular Record of Movement for CD-30, at: http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-30_t.htm

Account of 24 July 1945 as 7th raid on Osaka (by Japanese account): https://jinken-kyoiku.org/heiwa/o-kuusyuu7.html

The Osaka End of the Line for the Crew of the “Indian Maid”

Although they started out on June 5th, 1945 in daylight for Kobe, it was near Osaka where the (remaining) crew of the B-29 “Indian Maid” met their fate at the end of the line.

On this June 5th mission (Mission 188) 473 XXI Bomber Command B-29’s attacked Kobe with 3,077 tons of incendiary bombs. The attack burned over four square miles and damaged more than half of the city. Fighter opposition was significant; 125 enemy aircraft sighted made some 672 attacks. B-29 gunners claimed 86 Japanese fighters destroyed, 31 probables and 78 more damaged. Eleven B-29’s were lost including the “Indian Maid.”

The Fishkin crew flew B-29-51-BW serial number 42-24809 “Indian Maid” of the 482nd Bomber Squadron, 505th Bomber Group (Circle W group tail marking) based on North Field, Tinian Island.

First Lieutenant Robert W. Scheer reported on the Indian Maid’s loss in Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) 14603, “At 0830K on bomb run at 15,000 feet, Capt. Fishkin’s plane was flying #4 in the lead element of a fourteen plane formation. He was lower than usual. Two Tonys (Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien Type II Army fighters) attacked him at the nose and knocked out both engines on right side. Capt. Fishkin tried to pull up into closer formation but his #1 engine gave out and he left the formation in a shallow dive heading towards Kobe, over Osaka Bay with several enemy fighters after him. Later he was noticed in a tight spiral. The fuselage appeared to be on fire towards the tail and the plane was trailing smoke. The engines were not on fire. Didn’t see plane crash.”

Sadly, the survivors succumbed to the deadly care of their captors. The men were initially taken to the Imperial Japanese Kempei Tai military police HQ in Kobe, and thence to the Central District HQ in Osaka.

Of the 11-man crew, five were killed outright in the shoot down (Capt Edward Fishkin (pilot), FO Alfred V. Boulton (co-pilot) 2nd Lt Gerard J. McIntosh (bombardier), FO William H. Moore (radar operator) and S/Sgt John Driapsa (flight engineer) (all in the nose section), and six became POWs of the Empire. Of the six, four men were either executed, died from injury or disease, Sgt Osmond J. Hannigan (gunner), Sgt Joseph C. Kanzler (tail gunner) and S/Sgt Henry W. Sutherland (radio operator). One source (2Lt John J. Meehan (Navigator) in Find-a-Grave) indicated Lt Meehan was killed in captivity on June 5, the day of the shoot-down, or on June 20. Another source (Kennedy in Find-a-Grave) says that the Imperial Japanese Army reported three others as having died of disease “on or before” August 15, 1945. And the remaining two, Sgt. James N. Fitzgerald (Right Gunner) and Sgt. Harvey B. Kennedy, Jr., (Left Gunner) met a grim fate near Osaka on or about this day in history, on 20 or 21 July 1945.

See the crew picture of the “Indian Express” at: https://pacificwrecks.com/aircraft/b-29/42-24809.html

A month after the “Indian Maid’s” shoot down, on July 5, 1945, five unidentified American POWs from the Osaka area were taken to the Shinodayama Military Maneuver Grounds near Osaka and executed by the Kempei Tai. This was a prelude to a larger POW massacre there which involved Sgts Fitzgerald and Kennedy. Details of this and other Osaka area POW executions are found in the legal document in references below.

On July 19, the foreign nationals prisoner sub-section of the Osaka Kempei Tai headquarters was detailed to send a work party to make preparations for another execution at Shindoyama, digging a mass grave next to the site where the first five POWs were killed and buried two weeks prior. The order came from the Fifteenth Area Army Commander’s headquarters in Osaka for 15 Airmen to be executed for the crime of indiscriminate bombing. This headquarters had absolute authority over the management and disposal of American flight personnel in the vicinity of Osaka. In postwar investigation of this incident, it was found that a Lt Col Hideo Fujioka, Chief of the Police Affairs Section of the Central District (Osaka) Kempei Tai, passed along the order to a Major Shiuchi in charge of his Foreign Nationals sub-section.

On the day of execution, two Airmen from the Kempai Tai detention barracks and 13 more from the 22nd and 23d units were taken by truck to the execution site. Bound and blindfolded, they were seated in front of the mass grave. Lt Col Fujioka watched as Maj Shiuchi selected the soldiers for the firing squad. The executioners were provided with US Army .45-caliber pistols which they locked and loaded at Maj Shiuchi’s command before proceeding to the front of the grave. Then Fujioka read the death sentence order, translated by Master Sergeant Mori. Both Fujioka and Shiuchi participated in the execution; Fujioka directed the executioners to shoot the prisoners in the forehead, then gave the order to fire. The prisoners were executed, their bodies placed in the grave which then was carefully hidden, with Fujioka ordering the soldiers to keep the execution a top secret.

But the secret was eventually found out after the war; between 15-18 April 1946, the bodies of the 15 men killed on July 20 and the five killed on July 5 were exhumed by US occupation personnel. Ten of the 15, including Sgt Fitzgerald and Sgt Kennedy, were identified.

In July, 1946, the former commander of the Fifteenth Area Army, Lt General Eitaro Uchiyama was arrested by American occupation military authorities. He was charged with war crimes and found guilty for allowing through his own acts and the acts of his subordinates the deaths of about 45 American airmen shot down in the Osaka area between April to August 1945. He was tried in 1948-1949 and sentenced in January 1949 to 40 years imprisonment at Sugamo Prison. But he was paroled in 1958 and lived until the age of 86 in 1973. It’s unknown at this time to the writer of this web log what happened to the junior officers directly involved in these murders.

Before that though, the remains of the Shinodayama victims were repatriated. Sgt James M. Fitzgerald was subsequently buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery, Manchester, Kennebec County, Maine. Sgt Harvey B. Kennedy, Jr.’s body was interred in the Yokohama Cemetery in Japan (likely Sgt Fitzgerald’s body was too) and repatriated back to San Francisco USA in late 1946 with the remains of 36 other fallen aboard the US Army Transport Dalton Victory. He was buried in the Sarasota Memorial Park in Sarasota, Sarasota County, Florida.

These Airmen executions are another part of the grim wartime air raid experience of Osaka. Hopefully some of the unidentified Airmen killed in these murders have been identified since then. Given the use of DNA in forensic analysis these days by the Defense POW.MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), it is possible.

References:

Kobe mission information, 5 June 1945: https://user.xmission.com/~tmathews/b29/56years/56years-4506a.html

Indian Maid noseart picture at: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/80-G-K-02000/80-G-K-2982.html

Indian Maid info and crew picture at: https://pacificwrecks.com/aircraft/b-29/42-24809.html

Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) 14603, B-29 42-24809

Sgt Fitzgerald: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/94941758

Sgt Kennedy: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/142067086/harvey-brown-kennedy

Lt. Meehan: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3785045

General Uchiyama picture at: http://www.qulishi.com/article/201809/298964.html

Record of the Joint and Common Trial of accused Japanese personnel charged with violations of the Laws and Customs of War related to treatment of American prisoners in the Osaka area 1945: https://www.online.uni-marburg.de/icwc/yokohama/Yokohama%20No.%20T328.pdf (note: 200MB file)

THE FIRST OF THREE: THE FIRST PRECISION ATTACK ON OSAKA

With most major urban areas having already been devastated by maximum effort incendiary bombing raids, XXI Bomber Command’s strategic air campaign in Japan shifted to smaller-scale incendiary attacks on smaller cities as well as precision attacks against certain war industry targets. In Osaka’s case, this resulted in three significant B-29 precision attacks on industry which commenced on June 26, 1945.

On this day, 75 years ago, 510 B-29s and 148 P-51s flew missions against the empire, in nine separate attacks. For Osaka it was a double strike, two precision targets in the metro area were hit. Mission 223 saw 64 B-29s of the 58th Bomb Wing with P-51 escort hit the Sumitomo light metal industry on the western side of the city. The B-29s hit the target between 1026K and 1202K; they dropped 382 tons of bombs by radar from between 19,600 and 25,300 feet through a 10/10 cloud deck.

The Superfortresses employed large high explosive bombs, AN-M56 4000-lb large capacity bombs with instantaneous nose and non-delay tail fuses. Due to the weather and use of radar the desired precision was not attained and only about 11 percent of the Sumitomo roof area was destroyed or damaged. Defending anti-aircraft fire was heavy caliber, meager to moderate in intensity and inaccurate to accurate. With an escort of P-51s, including one formation observed in target area, enemy aerial opposition was not a problem. The B-29s saw five enemy aircraft make five ineffectual attacks.

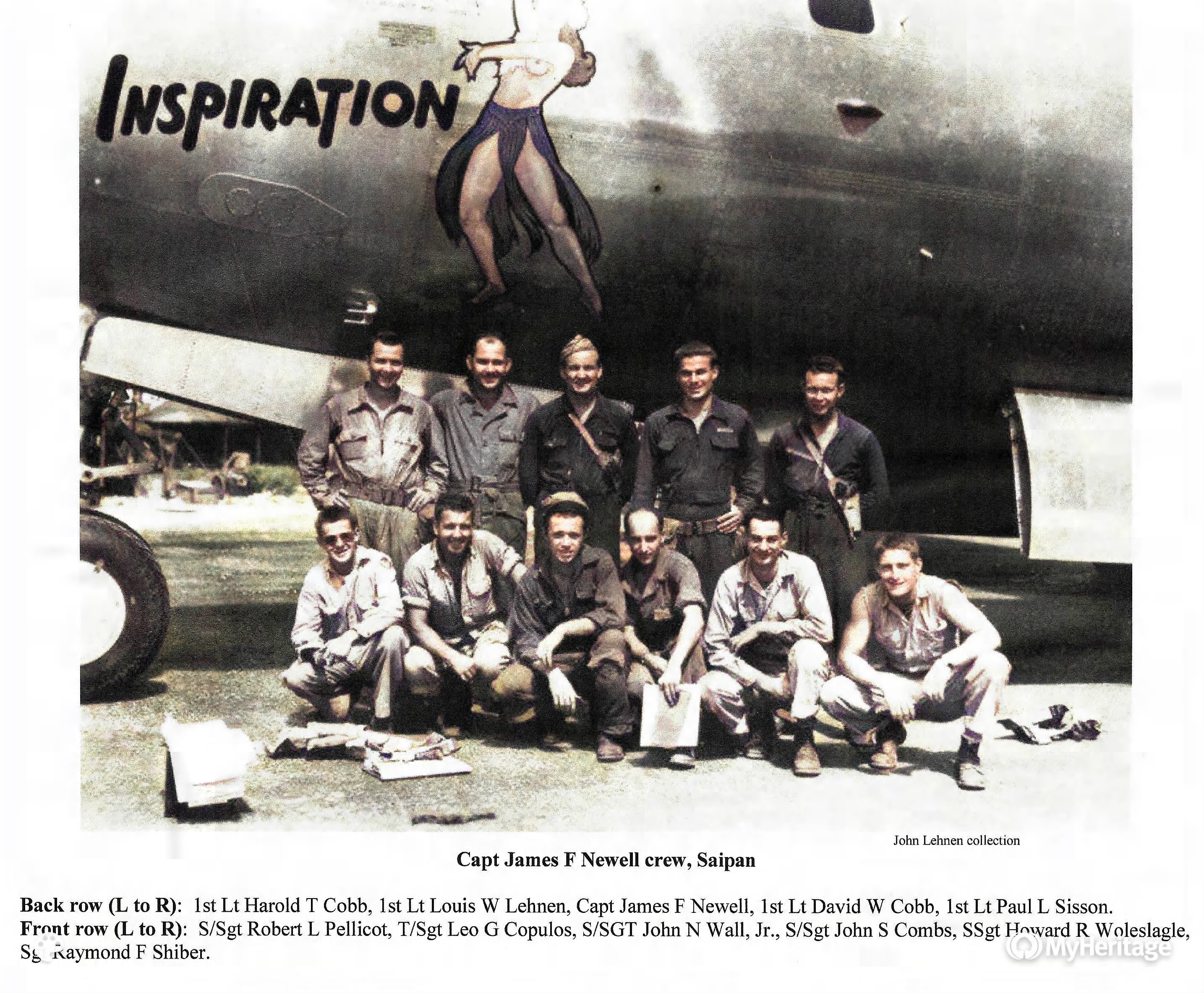

One B-29 was lost when serial number 44-69655 of the 499th Bomb Group (V square or large V tail markings), 877th Bomb Squadron (Newell crew) was shot down by Japanese fighter over Miyama Village in Hidaka County, Wakayama Prefecture after bombing Osaka Army Arsenal. (See MACR 14911). The aircraft was supposed to lead the second combat squadron of the group, but the formation was impacted by instrument flight conditions at the assembly point so never organized as planned. The aircraft wasn’t observed by others in the group and last heard from by VHF radio asking for instructions at the assembly point.

Two of the crew were killed in the shootdown, and nine captured and taken to the Kempeitai headquarters in Osaka. None of the captured airmen survived their captivity, however, and all were executed.

Seven are listed as executed with day unspecified in the mission summary at link below, with one killed on August 5th and the last man of the crew, 1st Lt. Harold Cobb, killed at Sanadayama Military Cemetery in Osaka City on the last day of the war, 15 August 1945. The fallen crew left five wives behind in addition to their family of origin members.

P-51s escorting the Osaka attack and also Nagoya, claimed 2 Japanese aircraft shot down and five damaged for the loss of one P-51 – the pilot ran low on fuel, bailed out and was picked up by a rescue submarine. Kawanishi N1K “George” Navy fighters were reported in at least two of the escort’s aerial encounters, one of which is described in a 504th Fighter Group summary: “During this entire operation, encounters with enemy fighters were extremely meager, on the blind alley run to Osaka, a couple of bandits were sighted out of range by the 462nd (Fighter Squadron). Since our job was to stick with the bombers, pursuit of the distant enemy was not undertaken. A bit later on the same course, 2 Georges offered themselves for sacrifice about 1500′ below our formation.

Capt Norman Miller’s flight pounced for the kill. Hits on one of the Georges — the other having fled into the clouds — were scored by Capt Miller and Lt Colley; the Nip disappeared straight down, smoking.” In general though, Japanese fighter opposition was insignificant: “Commenting on the mission, the Fighter Command, shaking its heed ruefully, observed that, “The reluctance of the enemy to send up his fighters when an overcast is present over the target area was again demonstrated.””

Eight and 14, respectively, of the B-29s from the double strike recovered at Iwo Jima on the way back to their bases in the Mariana Islands.

In summary, these intended precision attacks were not very precision due to the weather. But damage was done, including some 5,351 buildings destroyed, of which only about three percent were industrial. However, the lack of damage to the intended targets meant that the B-29s would once again visit Osaka. And these would not be the only Allied aircraft to visit the Osaka metro area in the remainder of the war, also a tale yet to be told here.

References:

Summary of Missions 223 and 234 at: https://user.xmission.com/~tmathews/b29/56years/56years-4506b.html

Effects of Air Attacks on Osaka, Kobe, Kyoto at: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/NHC/NewPDFs/USAAF/United%20States%20Strategic%20Bombing%20Survey/USSBS%20Effects%20of%20Air%20Attack%20on%20Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto.pdf

506th Fighter Group VLR Missions to Japan, at: http://www.506thfightergroup.org/iwotojapan.asp?ID=2

Kawanishi N1K2 box art, at: https://www.1999.co.jp/eng/10270788

Sumitomo history at: https://www.sumitomocorp.com/en/jp/about/company/sc-history